A brief history of watchmaking from the 14th century to the present day.

A journey through the socio-economic and technological events in Europe that have influenced the progress of watchmaking.

The rise of the mechanical clock

There is no evidence of who invented the mechanical clock or exactly when it first appeared. The earliest literary reference to a mechanical clock is reported by Dante Alighieri in his Divina Commedia (written between 1308 and 1321), where the poet mentions in the Canto X of the Paradise a clock made of gear wheels and the sound of a bell announcing the passage of time.

In 14th and 15th century Europe, mechanical clocks became ubiquitous in towers, but also in churches, royal palaces or governmental buildings. They set their time against sundials and were connected to bells that struck the hours. In 1337, Galvano Fiamma (1283-1344), an italian dominican chronicler of Milan, tells us that the first mechanical clock in the city of Milan - also believed to have been the first one in Italy - was installed in the tower of the church called San Gottardo in Corte.

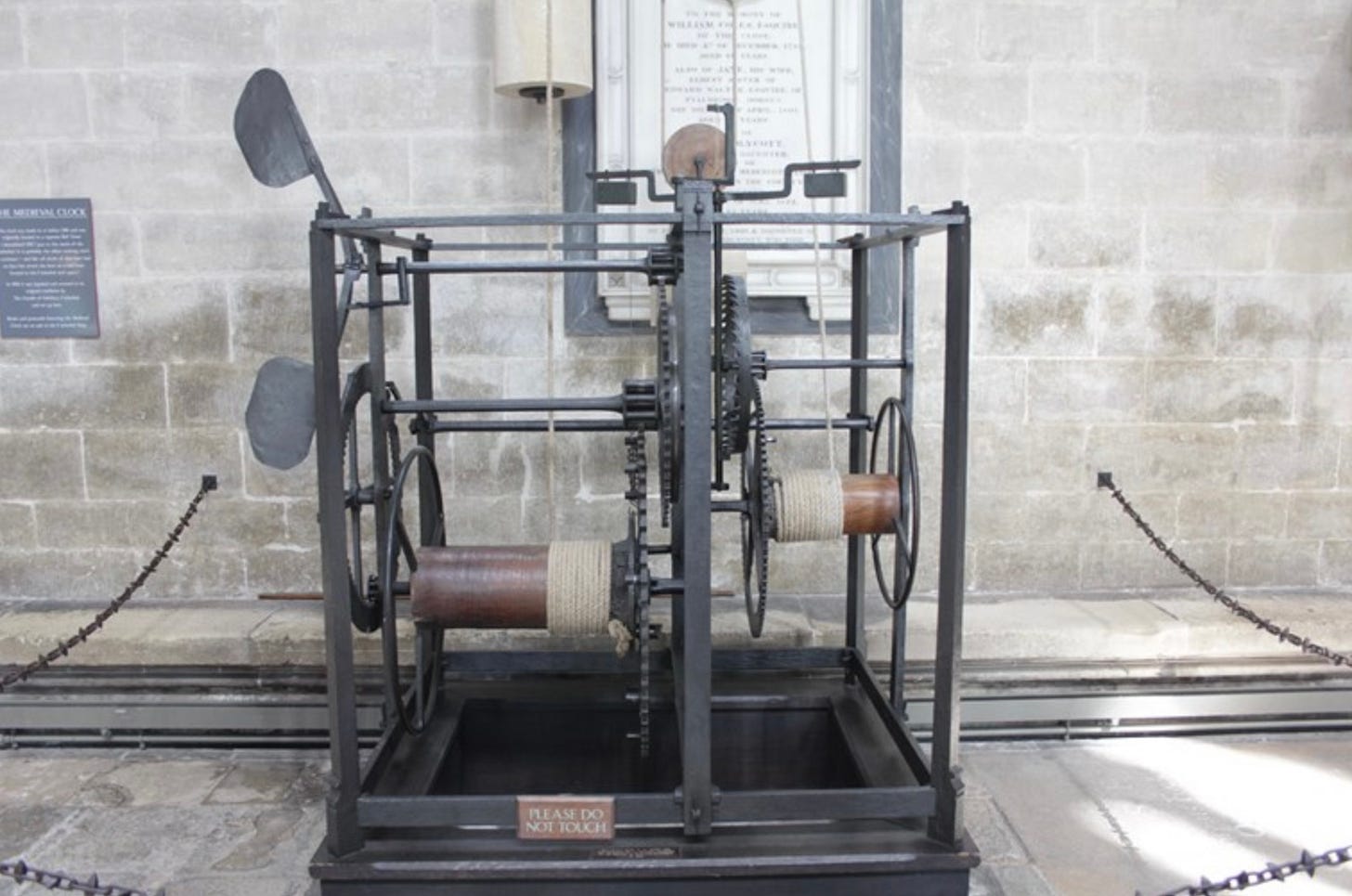

The clocks of this period, such as the one in the San Gottardo in Corte, were weight-driven (i.e. using falling weights) and wound up periodically, once a day or once a week. They were the result of improved skills in metal working by locksmiths and clockmakers and of improved ability in making metal components, which were stronger, more flexible, and of more sophisticated shapes. Such clocks were made of iron and later in the 17th century clockmakers began using brass, because unlike iron, it did not rust and it was easier to work with (Fig. 1).

In the early 15th century, dials began to appear on clock towers. The dials displayed the hours with an hour hand and often also included information on the positions of stars and planets and moon phases. At times the towers were adorned with automata representing the act of sounding the bells, a very good example is the clock tower of San Marco, in Venice. The timekeeping was still very inaccurate.

Fig. 1 - The Salisbury Cathedral Clock is the oldest surviving working mechanical clock (1386)

From clocks to pocket watches

In the early 1500s, the German clockmaker Peter Henlein (1485-1542) is credited as being the inventor of the portable watch, or small ornamental timepieces, which could be worn as neck pendants, encased in rings, hanging from belts, or kept in pockets. In 16th and 17th century Europe, portable watches were used as a display of status quo by the clergy, the nobles, the ruling classes, and the royal entourages. Their cases were made of octagonal, oval, round, or drum shapes, and had beautiful high quality decorations and finishing (Fig. 2). By the 17th century, the style was mostly for men to wear these portable watches in their pockets.

The scientific progress made possible by the Renaissance with its cultural, artistic, political and economic “rebirth” following the Middle Ages, the age of discovery which began in the 15th century and led to several important explorations and discoveries of new worlds and riches, as well as the copernican revolution were key in stimulating the need for more precise instruments of measurements in several disciplines such as astronomy, geography, physics, and mathematics.

In astronomy, Jost Burgi (1552-1632) was the first to measure the second as a unit of time, enabling more precision in the observation of celestial bodies. Not only a clockmaker but also a polymath, in 1585 he developed a clock movement that displayed the hours, minutes,and seconds on three separate dials and considerably reduced the daily error in the measurement of time.

Following Burgi’s innovation, Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) conceived a clock movement that used a pendulum, which was further refined by Christian Huygens in 1657 improving accuracy from a daily error of ca 15 minutes to 15 seconds. And in 1675, Christian Huygens introduced the balance spring, an innovation which significantly changed the path of horology, making it possible to further miniaturize timepieces and considerably improve their accuracy. Eventually, in the late 17th century, English clockmaker Daniel Quare (1648-1724) developed a dial with concentric hour and minute hands giving timekeeping the face that we are mostly familiar with today.

Fig. 2 - Foto of a portable watch so-called “Onion” because of its shape, from the late 17th century. Foto from Musee International d’Horlogerie, La Chaux-de-Fonds, Switzerland.

Horology during the Age of Enlightenment

In Europe, the 18th century was a period of intellectual, social, and political ferment. This time is often referred to as the Age of Enlightenment, for it was in the 18th century that the ideas of the previous 100 years were implemented on a broad scale. This is also true for the field of horology. Improvements in the quality of steel during this period enabled further accuracy and miniaturization in the making of clocks and the development of the maritime chronometer is considered by many the most representative contribution to horology during this period.

After the great discoveries and explorations of the 15th and 16th centuries, European states were ready to do anything to control the maritime routes and bring back the colossal wealth of the new colonies. But empirical and imprecise methods in measuring time at sea and distance traveled lead to errors that repeatedly resulted in dramatic shipwrecks. On October 22, 1707, four British warships ran aground on the Isles of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall and nearly two thousand marines lost their lives without fighting.

The Longitude problem in the early 18th century consisted in the lack of accuracy and reliability of clocks when used in difficult working conditions at sea with changing temperature, humidity, and pressure. A clock that was a few seconds too fast or too slow could result in the ship ending up several kilometers off course. There was a need for a clock that could tell the right time at sea. This led to the Longitude Act in 1714, when the English parliament awarded a prize in money to whoever would find a precise method for the exact determination of a point at sea.

After much experimentation, in 1761 John Harrison (1693-1776) was the first to develop a chronometer, the H4, a large pocket watch, which during a navigation between Plymouth and the island of Barbados allowed the measurement of the longitude with a total distance error of only 9.8 miles. This was the birth of the maritime chronometer which solved the longitude problem and allowed John Harrison to win the Longitude Act prize.

Fig. 3 - John Harrison’s H4 Chronometer and its movement (National Maritime Museum, London)

The industrialization of watchmaking: the 19th century

In 1769, James Watt (1736-1819) unveiled to the world the steam engine, an invention which transformed human society from an agrarian/religious economy where work was regulated by the sun, the moon, and the seasons to one where work was regulated by accurate timekeeping.

The steam engine and the steam locomotive kick started a new era in transportation and travel. With railroads linking together entire continents, nations were replacing hundreds (or even thousands) of diverging local times with a system of hour-wide time zones. Later in 1884, the International Meridian Conference in Washington D.C. selected the meridian passing through Greenwich (0 degrees longitude) as the world standard prime meridian and the basis for the global system of time zones.

The Industrial Revolution (1760 to about 1820-1840) led to the development of mass production of clocks and portable watches in the United States first, and then in Europe, in Germany, France, and England. The American watchmaking industry was soon able to produce more and better movements as well as cheaper timepieces than its European counterparty. Towards the end of the 19th century however, manufacturing centers in Europe began applying the American principles of industrial production in their factories and raised the competitiveness of their own watch manufacturing.

The socio-economic and scientific progress that came with the Industrial Revolution pushed the need for accurate timekeeping to fractions of a second. Several horological innovations addressed the need for more accuracy. One notably had the greatest impact on a society that was now much more dependent on activities regulated by team keeping: the invention of the chronograph by Louis Moinet (1768-1853) in 1816, which he used for astronomical purposes. Later in 1821, Nicolas Mathieu Rieussec (1781-1866) created an improved chronograph for King Louis XVIII, to measure elapsed times at horse races, a favorite pastime of the King.

Progress made in metal working and research in precision horology led to the invention of Invar (1896) and Elinvar (1913) by Swiss physicist Charles Edouard Guillaume (1861-1938), two alloys with low coefficient of thermal expansion, used in balance springs, which significantly increased the accuracy of mechanical watches and chronometers, as well as of other scientific instruments.

Fig. 4 - The first ever chronograph by Louis Moinet - 1816.

The quartz crisis and the rebirth of traditional watchmaking

By the end of the 19th century the pocket watch had reached its apogee. The 20th century saw the rise in popularity of the wristwatch over the pocket watch. By the 1930s, the wristwatch had taken over 50% of the pocket watch market. In this decade, the export of Swiss made watches comprised 65% of wristwatches and 35% pocket watches. In the 1940s and 1950s, the chronograph wristwatch came back to popularity, as a result of its practical use in WWII, as well as self-winding wristwatches with a power reserve indication, complications such as the calendar, moon phases, and the perpetual calendar. In the late 1950s and in the 1960s, space exploration brought wristwatches that could endure space conditions: Omega, Breitling, Bulova, and the Russian Sturmanskie were worn by astronauts during their space walks or on the moon.

And then came the quartz revolution. In 1969, Seiko launched the Astron 35SQ, the first quartz wristwatch in the world, which marked the beginning of the quartz crisis. The Seiko Astron was the result of scientific and technological progress that had its roots since the 1920s in the US. Its technology was 100 times more accurate, as well as much cheaper than a mechanical watch and it brought accurate timekeeping within reach of all. By 1978, quartz wristwatches had overtaken mechanical wristwatches in popularity and had plunged the Swiss watch industry into a deep crisis. Before the 1970s, the Swiss watch industry had prospered in the absence of any real competition and held 50% of the world watch market. Between 1970 and late 1980s however about a 1000 Swiss watchmakers did not survive the crisis and went out of business, while in similar periods employment in the industry fell from 90’000 to 28'000 units.

Fig. 5 - The Seiko Quartz Astron 35SQ. When launched, Seiko advertisement run with the ad: “Someday all watches will be made this way”

The quartz revolution drove several Swiss manufacturers to seek refuge in the higher end of the market. In order to survive, brands like Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet, and Rolex shifted focus from precision to technical creativity and luxury. Mechanical wristwatches gradually became luxury goods, appreciated for their elaborate craftsmanship, aesthetic appeal, and glamorous design, sometimes associated with the social status of their owners, rather than simple timekeeping devices.

In the late 20th century, new materials found their place in the creation of luxury wristwatches. Taking inspiration from other high-performance industries, watch brands experimented with materials both for the movement and cases as well as bracelets. This was in a constant search for lightness (e.g. carbon and titanium), corrosion resistance (tantalum and ceramic), strength and hardness (titanium and ceramic), and reducing the need for lubrication (silicon and synthetic diamonds). A trend which is still ongoing today.

The rise of independent watchmakers has colored the watchmaking industry in the early decades of the 21st century. From the mid-90s through to our days, watchmakers like Max Busser, Philippe Dufour, F.P. Journe, and Richard Mille to name a few established themselves as artisanal watchmakers introducing a creative approach to the development of watchmaking art. Often limiting their production to a few timepieces a year, their creations are sought after and purchased by collectors and enthusiasts around the world. These independent watchmakers opened new avenues for mechanical watchmaking with their experimentation of new materials, with their technical inventions and innovations, with their more novel, original, and visionary design choices, pushing the boundaries of precision and bringing back the beauty of hand-finishing, exceptional craftsmanship and establishing a refreshingly closer and personalized relationship with their customers.