Time ticks forward, unimpressed by our attempts to capture it in gears and circuits. For millennia, we have chased the seconds with increasingly elaborate contraptions, as if by measuring time we might somehow master it. Horology—the art and science of timekeeping—stands as perhaps our most enduring technological obsession, one that has evolved not merely as a practical necessity but as a mirror reflecting our shifting values, anxieties, and pretensions.

The Digital Disruption

The late twentieth century witnessed quartz technology dethroning the mechanical masterpieces that had reigned for centuries—a disruption driven not merely by technical innovation but by profound economic forces. The 1970s oil crisis and subsequent global recession created market conditions where affordable accuracy trumped traditional craftsmanship. Japanese manufacturers like Seiko and Citizen, backed by their nation's industrial policy and export-driven economic model, flooded markets with quartz watches at price points that devastated the Swiss industry. This "Quartz Crisis" (1975-1985) eliminated nearly two-thirds of Swiss watchmaking jobs—economic darwinism expressed through oscillating crystals.

Corporate consolidation followed as conglomerates absorbed failing traditional manufacturers. These business pressures transformed consumer expectations; as middle-class purchasing power stagnated across Western economies, the promise of "precision without effort" at accessible prices resonated with increasingly time-stressed workers. The second hand no longer swept; it ticked with digital certainty, each movement reflecting the broader socioeconomic shift toward efficiency, standardization, and cost management.

The analog dial gave way to the LCD display, numbers stripped of romance and ritual, mirroring corporate accounting's triumph over artisanal values. Time became data—raw, unadorned, utilitarian. The Casio calculator watch, emblematic of Japan's technological ascendancy and export dominance, adorned the wrists of the technocratic vanguard. This transformation reflected not merely changing aesthetics but the financialization of Western economies and the rise of managerial capitalism obsessed with measurable metrics.

The Digital Paradox

The smartwatch arrived not as revolution but as an evolution of our expanding technological dependency. Swiping through notifications while monitoring our heartbeats, we entrusted these devices with tracking not just hours but steps, calories, sleep cycles—the quantified self reduced to metrics and trends. How curious that as we became increasingly disconnected from our physical existence, we became obsessed with measuring it.

Apple, Samsung, and Fitbit transformed the wrist into yet another outpost of the digital empire. The pulse beneath the watch now mattered only as data to be analyzed, not as the rhythm of a life being lived. Our watches grew smarter as we, perhaps, grew less attentive to the passage of time itself, constantly distracted by the very devices meant to help us manage it. The smartwatch exemplifies our peculiar modern paradox: technology that simultaneously connects and isolates, informs and overwhelms.

Status on the Wrist

Throughout this digital renaissance, mechanical watches stubbornly refused extinction—not through technical superiority but through strategic business reinvention orchestrated by industry executives like Nicolas Hayek of the Swatch Group. The Swiss industry's salvation came through deliberate market repositioning: mechanical watches ascended to the realm of luxury precisely when global wealth inequality began its steep climb in the 1990s. The expanding financial sector created a new class of high-net-worth individuals seeking status differentiation exactly as traditional luxury goods manufacturers consolidated into conglomerates like LVMH and Richemont.

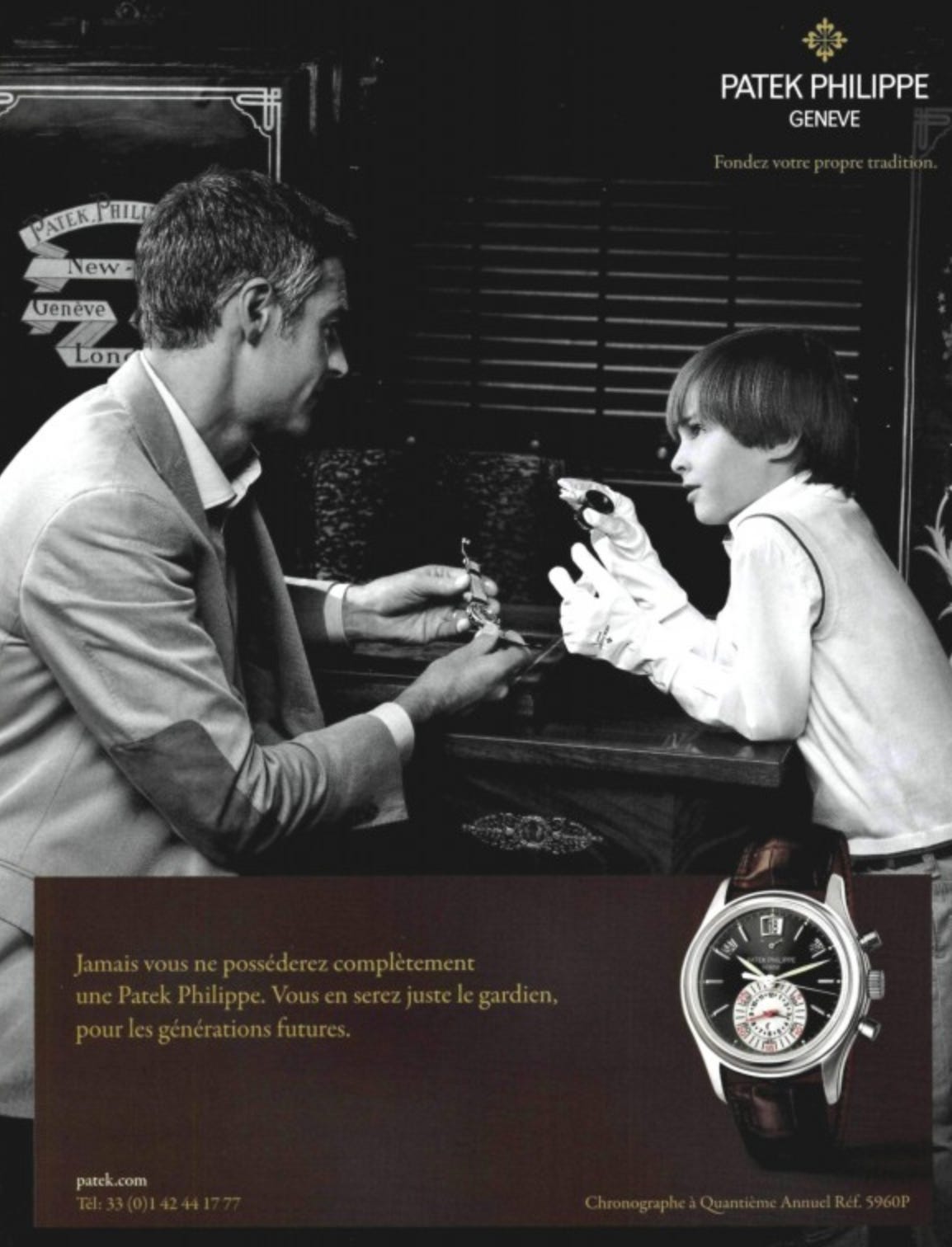

Patek Philippe's famous advertising campaign—"You never actually own a Patek Philippe, you merely look after it for the next generation"—was no mere poetic flourish but a calculated marketing response to both the emerging wealth transfer to baby boomers' children and the post-2008 anxiety about financial stability. The campaign revealed the ultimate luxury in our disposable era: permanence guaranteed by multigenerational wealth.

The mechanical watch's transformation from functional object to investment asset paralleled similar trends in real estate, art, and other tangible stores of value—a direct consequence of loose monetary policy, financialization, and growing distrust of purely digital assets. The irony thickens: tools once made for workers became trophies for executives at precisely the moment when executive compensation packages exploded relative to average worker wages.

The watch industry, guided by luxury conglomerate business strategies, discovered that selling history and heritage generated margins that mere timekeeping could never achieve. Between 1990 and 2020, the average price of a luxury mechanical watch increased at roughly triple the rate of inflation—a price elasticity made possible only by unprecedented wealth concentration at the top. A Rolex or Audemars Piguet on the wrist signals not just personal taste but one's position within increasingly stratified economies. Time itself—once the great equalizer—became yet another arena for displaying the widening social hierarchies produced by late-stage capitalism.

The Artisanal Counter-Revolution

As digital screens dominated our attention, an unexpected counter trend emerged: renewed fascination with mechanical complications and hand craftsmanship. Independent watchmakers like F.P. Journe and Philippe Dufour achieved cult status by creating timepieces using methods largely unchanged for centuries. This renaissance of traditional horology paralleled similar movements in food, fashion, and furniture—a collective yearning for authenticity in an increasingly synthetic world.

This neo-traditionalism reflected a growing disillusionment with mass production and planned obsolescence. The mechanical watch, with its potential for infinite repair and restoration, stood in opposition to the disposable electronics filling our landfills. Yet one must wonder whether this appreciation of craftsmanship represented genuine resistance to consumerism or merely its more sophisticated form—the same acquisitive impulse clothed in the language of heritage and sustainability.

Global Timekeeping

The geography of horology shifted dramatically as well, following broader patterns of global manufacturing redistribution and the rise of Asian economic power. Switzerland maintained its symbolic centrality through aggressive intellectual property protection and "Swiss Made" regulation—legal frameworks designed to preserve European market dominance despite production economics favoring Asian manufacturing. This represented a microcosm of how Western economies transitioned to emphasizing intellectual property and brand value while outsourcing production.

Brands like Seiko and Grand Seiko challenged the Swiss monopoly on horological prestige, their rise directly paralleling Japan's economic ascendancy and cultural soft power. Meanwhile, Chinese manufacturers, emerging from economic liberalization policies that transformed global supply chains, democratized access to mechanical watches—a horological expression of China's broader manufacturing revolution that reshaped global consumption patterns.

The internet's disruption of traditional retail manifested powerfully in horology. Online marketplaces like Chrono24 and forums like WatchUSeek created a global community that bypassed traditional gatekeepers through disintermediation—the same force that reshaped everything from book selling to travel agencies. Information asymmetry, once a cornerstone of luxury pricing models, eroded as enthusiasts shared knowledge previously guarded by authorized dealers and auction houses. This democratization threatened established retail distribution networks while simultaneously expanding the total addressable market for timepieces across all price points.

Yet even as horology became more globally diverse, the industry remained stubbornly stratified—a reflection of how globalization paradoxically increased both access and inequality simultaneously. The watch on one's wrist still signals one's place in the global economy—whether a mass-produced Casio assembled in Thailand, a middle-class Swiss-assembled timepiece with Asian components, or a plutocratic Patek Philippe representing the apex of global luxury consumption. Even time itself, it seems, cannot escape the economic stratification that defines our global economic order.

Sustainability's Slow Tick

The environmental reckoning that transformed so many industries has only recently begun to influence horology. Recycled metals, solar-powered movements, and plastic recovered from oceans have made tentative appearances in collections from both established and upstart brands. The circular economy found natural expression in the booming vintage watch market, where timepieces acquire new owners without requiring new resources.

Yet sustainability in watchmaking remains more marketing narrative than industry transformation. The fundamental contradiction persists: the most sustainable watch is the one you already own, not the new "eco-friendly" model being promoted. The industry continues to rely on resource extraction, energy-intensive manufacturing, and global shipping networks while selling nostalgia and permanence.

The growing vintage market represents both promise and paradox—reducing the need for new production while simultaneously fueling speculative bubbles that transform timepieces into investment vehicles rather than functional objects. When a steel Rolex Daytona commands higher prices used than new, we witness not sustainability but commodification wearing its mask.

Time's Horizon

As we peer into horology's future, we see familiar tensions playing out in miniature. The mechanical watch—a technology perfected in the 19th century—has survived alongside quantum-accurate atomic clocks and networked devices that sync to the millisecond. This coexistence suggests something essential about our relationship with time and technology: we desire both precision and poetry, efficiency and beauty, innovation and tradition.

Our timepieces will likely continue this dualistic evolution, becoming simultaneously more technically advanced and more emotionally resonant. The smartwatch may incorporate more traditional design elements while the mechanical watch adopts subtle technical innovations that preserve its soul while enhancing its performance. The watch industry, perpetually caught between yesterday and tomorrow, mirror's humanity's broader struggle to reconcile our heritage with our ambitions.

Perhaps the enduring appeal of horology lies precisely in this tension. In a world accelerating toward uncertain futures, the steady beat of a mechanical movement or the reassuring glow of a digital display provides the illusion of control over time's relentless advance. We know, of course, that time cannot be truly captured or contained—only marked, measured, and occasionally admired as it passes.

If you enjoyed this exploration of how our watches reflect our society, consider subscribing to receive more articles at the intersection of technology, culture, and economics.

About the Author

Sergio Galanti is a journalist specializing in independent watchmaking and mechanical horology.